conversations – Interview by Anika Meier – 23.02.2023

HERBERT W. FRANKE & LEE MULLICAN: PIONEERS AND THEIR LEGACY

EARLY DIGITAL ART'S INFLUENCE ON NFTS

Interview by Anika Meier

Digital art pioneers Herbert W. Franke and Lee Mullican have been examining the connection between art and technology since the 1950s. Whereas Mullican saw the computer as an extension of his artistic vision, Franke saw this relationship as a cohesive one.

Cole Root, Director of the Estate Mullican, and Susanne Päch, Herbert W. Franke's wife, spoke with Anika Meier about the artists' legacies, their visionary spirits, and their influences on the current NFT space.

Herbert W Franke was a pivotal figure in the development of digital art, which he helped to shape over the next few decades as an artist, writer and curator. As early as 1957, Franke proved in a book entitled ART AND CONSTRUCTION (Verlag F. Bruckmann, Munich) that technology "opens up undreamed-of new artistic territory". He has consistently explored new territory with analytical methods and the assistance of machines for over 70 years, looking into the future of digital art until he arrived in the metaverse as an artist and curator in the early 2000s.

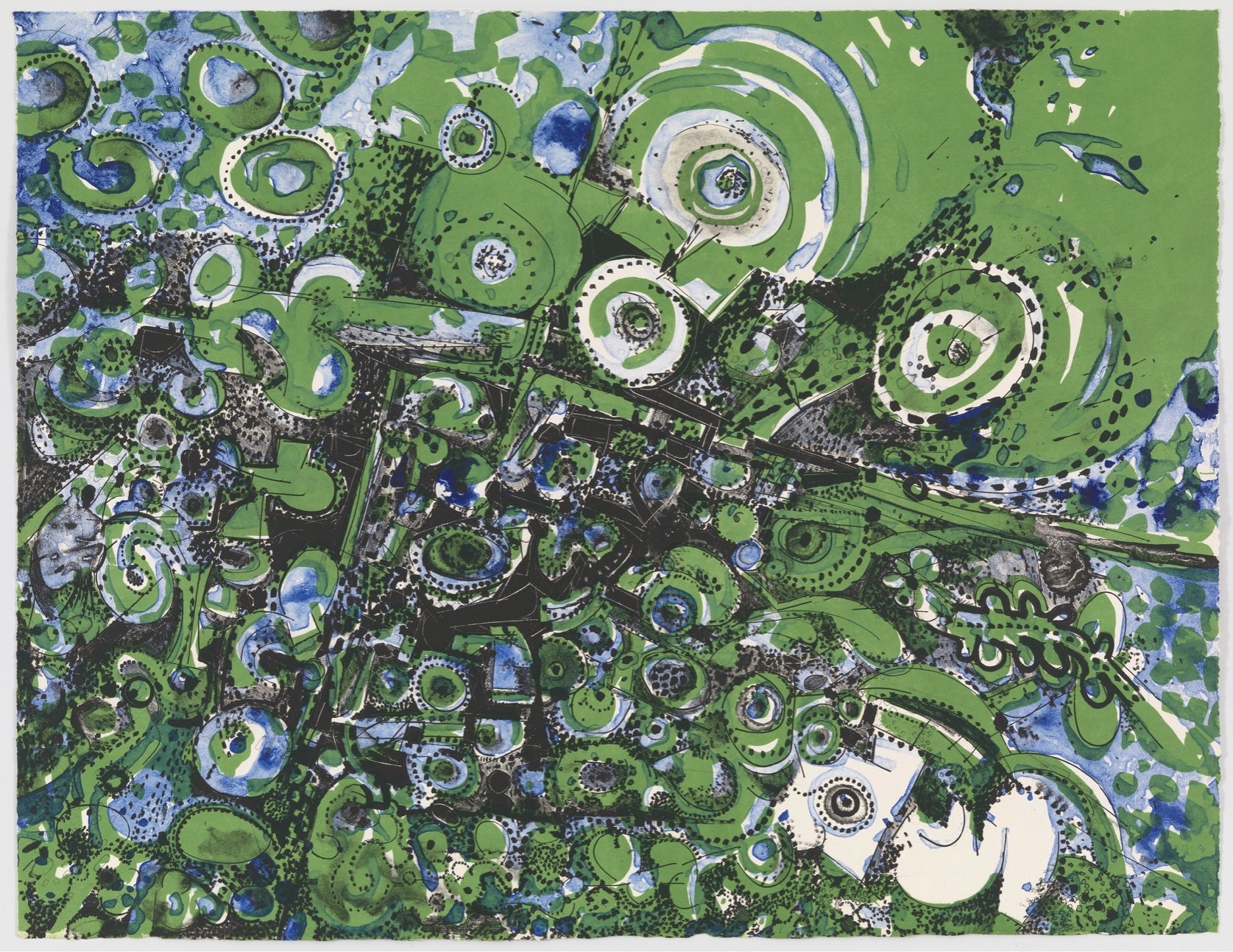

As a pioneer of digital art, especially in the USA, Lee Mullican has devoted his life to experimenting with various art forms. Mullican's paintings depict characteristically computer-like patterns and lines, emphasizing the artist's devotion to combining technology and art.

Anika Meier: Susanne Päch and Cole Root, you are both representatives of the Estate of a pioneer of computer art. How did you get involved with the work of each artist?

Cole Root: My background has been in art production and exhibition design. I worked at a small museum in St. Louis and then I worked for Matt Mullican as a studio assistant for a few years in New York. That's how I learned about Lee Mullican being a pioneer of computer art and about Matt Mullican being an early pioneer and experimenter in digital art, particularly VR. When I moved to Los Angeles the Mullican family needed help managing both Lee and his wife Luchita Hurtado’s careers, which is how I ended up working fully with them.

Susanne Paech: I am the wife of Herbert W. Franke. Herbert started creating digital art in the 1950s and was ahead of his time. He started working with analog photography but also worked with an analog computer already in the 1950s and then moved to digital computers in the 1960s. We are very new in the community of crypto art, entering approximately nine months ago when Anika Meier introduced us to the Twitter community. Herbert passed away in July 2022 and I’m left here on earth to move on. So, we – Herbert and I – are very happy to be part of the community now.

It was 1979 when I joined Herbert’s world, and from that time on, we’ve been part of it, which means from the beginning of the PC computer time onwards. We bought our first Apple computer in 1980.

AM: I saw Herbert's piano when I visited you at your home near Munich. You explained to me that he basically lived three separate lives for a very long time. Only with his solo show at ZKM (the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe) did he bring all three lives together: he explored caves, was a scientist, an artist and a curator, an art theorist, and a science fiction author. When it comes to his career, what would you say were his most important achievements?

SP: All his different activities have one common focus: his vision. He always wanted to look into the future, and he did it with science by developing new things, writing science fiction stories, and through art. New technologies fascinated him, and he wanted to see what he could do with them. From an artistic point of view, the trigger was exploring the aesthetic dimension of a machine.

I believe MATH ART is one of his most important works because it’s such an extensive series. I also see the Texas Instruments program for the TI 99/4 computer, which he wrote in 1979, as an important project. Herbert had to develop an art program for Texas Instruments, so he decided to do a running program: an interactive one and one with a sound part. He combined different art forms because he always saw the computer as a universal machine. It was important to him that digitization and digital computer art are not limited to visual art but are combinations of different sections of art, which can be stimulated with the same program.

AM: Cole, as the Director of the Estate Mullican, do you see any differences between how Lee Mullican, the pioneer from the United States, and Herbert W. Franke, the pioneer from Germany, approached different technologies?

CR: It’s exciting seeing the parallels between Herbert W. Franke and Lee Mullican. Like Herbert, Lee was also constantly experimenting. Throughout his career, he was a graphic artist and cartographer in World War II for the US Army.

After he left the army, he was in a constant search and researched his inner vision through art. He found art to be a spiritual and meditative practice and continuously wanted to expand that practice. He was constantly drawing and making sculptures out of wood, ceramics, and bronze. He was a creative writer and wrote plays and did experimental theatre. Computers were a new way for him to expand his creative footprint and the quest for inner vision through new means. There definitely are similarities between Lee Mullican and Herbert W. Franke in that way.

AM: What are the most important works of Mullican’s career?

CR: Lee Mullican’s most well-known work and the movement that defined him was the group called the Dynaton. It emerged out of the San Francisco Bay area in the late 1940s and that group consisted of Lee Mullican, Gordon Onslow-Ford, and Wolfgang Paalen. This group of artists was interested in incorporating surrealist methods, but they were also interested in art as a spiritual practice. They looked more at indigenous cultures’ art-making practices and how they are related ceremony. The Dynaton work of the late 40s is the most institutionally collected and well-known of Lee’s.

Lee started working with darker backgrounds in the early 1970s, which was when technology and computer screens started to be seen. Lee taught at UCLA for almost thirty years, during which time he started working with computers and was friends with people like John Whitney. He was always very interested in these emerging technologies, but it was challenging working with them before the rise of the PC.

SP: I can only agree. When Herbert started creating generative art in the 1950s it was extremely complicated to make. Additionally, the public didn’t notice generative art or care about it. That was a big obstacle back then. Today, there is more publicity around digital art in general – it may not be good publicity but at least it’s noticed. Herbert exhibited a large number of generative art series in the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna in 1959, but no one really knows about it. Despite a few local newspaper articles it’s totally forgotten.

AM: Nowadays, everyone has access to technology and is online. How was it back then? How did you get access to technology in the first place?

SP: Herbert worked together with a friend, who was able to build an analog computer. Gaining access to digital machines was difficult, though. Only institutions and big corporations had these technologies, but they were not open for public use. Through some connections Herbert made while working at Siemens, he was able to use these machines in the research lab for experimental aesthetic work during weekends or after hours. It was very difficult to get access to these machines before the time of the home computer. And then it was quite easy.

CR: Lee taught at UCLA for over 27 years and while he was there in the mid-1980s, they had a program called the Advanced Design Research Centers Program for Technology in the Arts. There they had the first PC-based computer lab for the Art Faculty, Lee was one of the only faculty interested in experimenting with computers. People told him that he was wasting his time and that he should be painting.

AM: Going through Herbert W. Franke’s and Lee Mullican’s archives and extensive work, I was wondering why people were not interested in collecting their art back then. This suddenly changed a few years back. Does this have to do with the rise of NFTs or simply because technology is more common?

SP: In my opinion, it is definitely related to the advent of NFTs. For some time, the NFT community was a bubble, not very interested in its own history. With Herbert and other pioneers of digital art, the crypto space started showing interest in the beginnings of it all that was outside the NFT world. After all, that is an integral part of the NFT space today.

CR: NFTs definitely were a catalyst for interest. What got me into the space was the fact that there are people who appreciate digital abstraction. We started using NFTs to educate people about Lee’s work and his role as a pioneer in digital art. We could show the work in its native digital format on the screen. We felt it was the right way to do the work and the purest way. I’m really happy that this catalyst happened.

AM: How did both artists develop their own body of work in relation to contemporary art while at the same time working with suitable technologies and developing something completely unique with new tools?

SP: Between Herbert’s work and traditional art there was not really a connection. Developing his own approach and using machines to create art, Herbert learned that he was more or less the only one doing that. Herbert thought that his experiments could be art and continued to follow his path. Herbert thought about the future of art, he thought of using machines to create visual art combined with music or poetry.

CR: Contrary to that, Lee was not particularly interested in technology, other than to have the means to show his patented painting style, which he developed in the late 1940s of using a palette knife to make these raised lines which he called striations of three-dimensional paint on the canvas. Lee also incorporated the surrealist method of automatism, where he would go into a state and kind of make a semi-automatic work. Through technology, he further developed his style and made changes to it, but when he arrived at the computer, he was able to use some of the same methods he used for his paintings.

AM: Susanne, you told me once that Herbert did art as an experiment because he wanted to solve a problem, which is why his body of work is so diverse.

SP: Creating art was like doing an experiment for him. Coming from science, he also approached art like a scientist. He viewed science as something beautiful and wanted to explore how machines can produce art. I would say his approach was very different from most of the artists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

AM: He saw the machine as a partner?

SP: Absolutely, Herbert wrote about that in 1957. He said the computer is a partner of the human artist; the artist is a constructor of art. Herbert also mentioned that machines will play an important role in making art in the future. In a way, he already predicted Artificial Intelligence vision and the discussions about machines taking over our lives and enter creativity in the 1950s.

AM: Lee Mullican worked as an artist for decades with shows across the US. Do you know why he has never received such recognition in Europe or elsewhere?

CR: I'm not sure why Lee was never so successful in Europe. He did have a couple shows in Germany in the 1980s and 90s. He was kind of pegged as a California artist, and during the 1940s and 1950s, Los Angeles was not the contemporary art center then that it is now. It was often seen back then as a place to “drop out.”

Lee saw his work as a spiritual practice and used his art as a recording of this process. For him, the most important part was doing the work and then setting it aside. He would fill whole pads of hundreds of similar drawings each day. I think this is like many generative and code-based artists—the code itself is the work, and for Lee, the making itself was the work.

AM: It seems it was the other way around for Herbert W. Franke – he was well known in Europe but not so much in the United States. Now suddenly the world is speaking about both artists.

SP: I don’t really know why his work wasn’t known. Herbert was known in America for his publications about computer art, computer graphics, trends, or other people, but his work never was the focus. He was not good at marketing himself, to say. He curated an exhibition for the Goethe Institute that traveled around the world to approximately 200 cities. This was a very big show with a lot of artists, including all the well-known pioneer artists. Herbert’s main focus was showing museums that computer art was significant, instead of his own work. Maybe that's an explanation.

CR: For Lee, when he had his first kind of major success, he was in his 20s. He had a solo show at the San Francisco Museum of Art as well as the Dynaton group show. Through the years, the galleries and the collector base were very interested in that early work and less focused on the new work, regardless of what kind of evolution or new strides he was taking. That was a big part of putting Lee’s digital work out in the world. If they came to see his work that way, maybe they would understand his later paintings and appreciate his influence more.

SP: I really think that America was further ahead in the openness to show these things than people were in Europe and in Germany. Europe is very traditional and was very boring concerning new things. The ground for that kind of work was much better in America than it was in Europe.

Herbert W. Franke (1927-2022) was a pivotal figure in bridging the gap between art and science. He was a scientist, author of science fiction, curator, mathematician, physicist, and speleologist. He was a co-founder of Ars Electronica in 1979. Franke has been called "the most prominent German science fiction writer" by Die Zeit, and a "great storyteller" by the FAZ. He also developed a rational theory of art. As a writer, he has been a pioneer of virtual worlds since 1960 – with his first work DER GRÜNE KOMET (Goldmann, Munich). In addition, he pioneered cave research with the dating of stalactites, with which he was also able to reveal significant information about climatology since the last ice age.

Lee Mullican was born in Chickasha, Oklahoma, in 1919 and died in Los Angeles in 1998. He is considered a pioneer in digital art and has been creating computer art since the 1960s. After winning a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1959, he spent a year painting in Rome before returning to Los Angeles, where he joined the teaching staff of the UCLA Art Department in 1961, keeping his position for nearly 30 years.

Mullican’s works are included in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Hammer Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as numerous other institutions.