conversations – Interview by Anika Meier – 18.08.2023

CHRIS COLEMAN: "THE DIGITAL IS AS EPHEMERAL AS FLOWERS"

Digital Art and 3D Scanning

What can contemporary art be in the digital age? Artist, curator, and collector Chris Coleman has been asking this question for almost 30 years. He is Professor of Emergent Digital Practices at the University of Denver, where he teaches code to students, among other things. Until the 2021 hype surrounding NFTs, digital art was niche. Has that actually changed in the long run?

In conversation with Anika Meier, Chris Coleman tells how he got into digital art and coding at an early age, how collecting digital art has changed, and why he captures the world around him using 3D scanning.

Anika Meier: You are an artist, professor, curator, and collector. What do your days look like?

Chris Coleman: Like most people, I sit in front of computers. They are where I am social, where I learn, where I share, and where I consume. I have a hard time not jumping from the tab where I am working on some creative code art to a tab where I am writing a grant, and then to the tab where I am learning the new software I plan to teach in a couple months, and of course the tabs where I check out other people’s art and share emojis.

AM: You are a Professor of Emergent Digital Practices. Do NFTs have an impact on your teaching and the perceptions of students about digital art? Or do you have the impression that news about market activities doesn’t reach universities?

CC: My students are mostly dismissive of NFTs because of the popular "bro" culture tied to them, along with their relationship to crypto currencies. Of the 100 or so students at the University I have talked to about NFTs, only 2-3 have wanted to have any sort of discussion about them. I also offered three workshops for young artists who might want to understand the marketplaces and engage with them, but only one student ever showed up.

I think the students see the digital arts as something they will apply to "real jobs" in advertising, digital promotion, and cultural production for companies and organizations. In the US, almost no one is attending a private University like ours and expecting to become a full-time artist; it simply is not realistic.

AM: As a professor, what would you like students to take away when they leave university?

CC: The confidence and desire to keep learning, the kind of curiosity that keeps them questioning how things work and why. The foundation of understanding is that nothing is simple and binary, history is fluid, and technology is not neutral. Every decision they make has consequences and power. That they can make the world even just a little bit better for someone else, and that is success.

AM: When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

CC: In the 5th grade, an artwork I made was chosen for some sort of regional award and shown in a giant hall behind an orchestra. Seeing your art that big and celebrated by hundreds of people was surreal.

Despite that, I pursued Engineering in college, like my father, stepfather, and grandfather. I imagined I would be designing cool things like toys, roller coasters, and rocketships. But then I found out that engineers are more likely to design things like the hook on the end of the rod that opens and closes window blinds. Two courses before I graduated, I dropped out of University and took a year to reset while working as the manager of a restaurant. I realized that the courses I loved and got the best grades in were the ones I took in the Theatre department, building props and sets for plays. I went back to school as a sculpture major with digital skills and never looked back.

AM: How did you get into creative coding?

CC: I was introduced to Macromedia Director by my teacher, artist Hassan Elahi, and then went on to make things with Flash. It was quite intuitive because of my experience growing up with a VIC-20 and later a Commodore 64, as well as doing some work in FORTRAN for my Engineering degree. I was immensely privileged to have a family that bought home computers and encouraged us to play with them. But I mostly poked and copied code until I was in graduate school at SUNY Buffalo, when I learned to program microcontrollers and took a class in C++. I came to understand the power that coding and interactivity brought to my art practice and wanted to teach others the same. I started learning Max in 2001, Processing in 2006, and OpenFrameworks in 2009, then bringing each of them into my classrooms as part of my own ongoing education. I am still not a very good coder, but I enjoy the challenge.

Right now I am about to teach three.js to a dozen students starting in a few weeks, following the rule that you just need to stay two weeks ahead of your students!

AM: You are both an artist and a collector. Before the NFT hype, digital art wasn’t in the news and headlines of media outlets all over the world. When it comes to the history of art, especially painting, this history is well known. I studied art history at the University of Heidelberg, and I remember that the only artist working with technology I heard about was Nam June Paik. The history of digital art hasn't really been taught at universities. What are your criteria for good digital art?

CC: At the start of the 21st century, I was lucky to have some professors already involved in digital art; some were members of The Critical Art Ensemble, others were part of the cyberfeminist collective SubRosa, and others, like Tony Conrad, had been playing with experimental digital audio and video for decades.

One of my tasks in 2001 was to transfer one of my professor's extensive VHS collections of artworks onto DVDs, and so I had a deep look into a broad cross-section of what contemporary art could be, especially when digital technologies are involved.

Good digital art is good art. I want art that is aware of and contextually purposeful with its medium. I want art that shows me something new about our world. I want art that asks hard questions and, even better, proposes how we can move forward and solve problems. I want art that brings me moments of joy, sadness, and curiosity. I want art that stays in my head and is even better when I see it again a year later.

Digital is a medium, a set of tools, and a huge part of our contemporary lives. This means that digital art has a unique role in speaking about our current and future existence.

AM: What do you recommend as a good starting point to learn about the history of digital art?

CC: Honestly, I do not know. I have books that try and fail to convey the actuality of digital art. Books are analog reproductions; they do not move, glow, or surround us the way good digital art does. Even videos are often nothing more than documentation and poor transfers of the artwork. YouTube is a source these days, but it is not organized to help you understand the connections and influences. There are other books that try to capture slices of digital art history, but so often they are driven by very personal perspectives and personal networks.

I teach a course on digital art in the 21st century and have been guiding students to write about the artwork and share it as a blog in an attempt to add to the resources available. I think we are still scattered, and I suspect there are great university syllabuses running around with threads of things to see and read.

I embrace the fact that our ongoing history can be fluid, and we continue to redefine who is or was important over time. But I also see much of our history as missing: lost on floppies and CD-Rs that are quickly decaying, websites full of broken links, and hardware that can never be replaced or repaired. I am honest enough to understand that my work as a digital artist is likely to be very ephemeral. And perhaps that is also okay.

AM: Is being the first important to you from a historical perspective? Or do you think the second mouse gets the cheese?

CC: Neither? In our field, being first is typically the person who makes a quick, funny tech demo. It is the person who spends months or years with a tool who truly starts to understand what that digital tool, process, or cultural moment is and what can be said with/from it. That is the art that is important.

AM: As an artist, you mainly mint your NFTs on the blockchain Tezos. How did you learn about NFTs and Tezos?

CC: I was drawn to Tezos and Hic et Nunc by the digital artists I followed on Twitter at the time. Specifically, I remember Marius Watz, Mario Klingemann, and Frederik Vanhoutte sharing work there. I had been trying to collect work from some of these artists for years, but it was never in my price range until then.

I had already been learning about tokenization on the early version of Foundation and continued collecting there when they re-launched as a curated platform. I was also a part of the second edition of Peer 2 Peer, which Casey Reas spun up to let artists trade work with each other, and I really found joy in that process.

AM: Were you skeptical at first?

CC: For sure. It took me a couple months to understand what kind of artwork I wanted to release as NFTs and how seriously to take this new marketplace. But the low cost of entry as a collector made me really excited to engage with a whole set of artists I had never been able to collect from via the gallery system.

That said, my wife Laleh Mehran and I have been collecting digital art since 2006 and have dealt with many methods of purchasing and archiving. We have also encountered many tactics that artists use to generate scarcity and control where their art goes. We are documenting some of it on a website, inspired by the Spalter Collection.

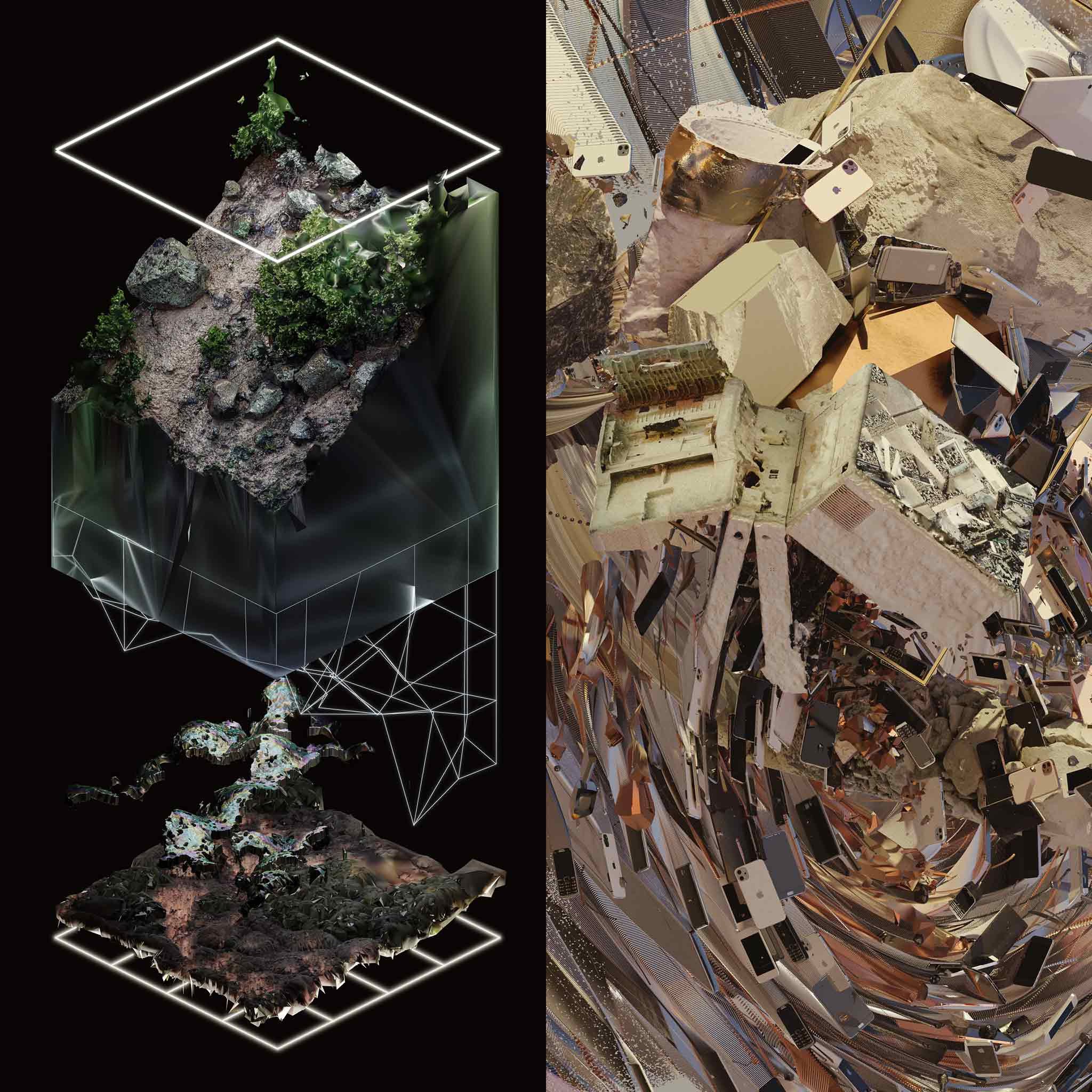

AM: As an artist, you explore 3D scanning. What are your learnings and findings?

CC: To answer this would perhaps require a whole book? Some notes:

- I have been scanning things for a bit over 10 years.

- I am very interested in the time involved in scanning and how it harkens back to old methods of photography.

- Scanning produces only an infinitely thin skin of the subject, a data layer lacking depth.

- The process of scanning is a dance, moving across arcs and planes to capture every angle.

- Scanning is interesting when and where it fails; exact digital replicas are boring and still fail to capture what is real.

- Each scanning technology is interesting in the ways it succeeds and fails, each trying to impose cartesian order in a different way.

AM: How do you decide what to scan? You, for example, scanned stairs near the Seattle Fish Market in 2021 for a series of artworks.

CC: As I get to travel, I try to scan whenever I can, perhaps as a form of memory? I like the way scans are fragments, removed from context. Perhaps similar to how we remember places and people. Many of the things I end up scanning are things I am seeing for the second time, and I realize that my memory did not capture them fully the first time. The pool of scans I have serves as a sketchbook, a pool of polygons and colors. They have meaning and context, and I am interested in how that context can be extended and expanded through digital manipulation.

AM: Do digital scans keep, for example, flowers alive?

CC: Like all digital things, there is a significant loss when something physical becomes transformed into binary, digestible for computation. Even in current imaginings of how we might upload the human brain into a digital system, they expect to destroy every neuron in the process. It has also become clear to me after making digital art for 25 years that the digital is as ephemeral as flowers; the time scales just differ.

AM: What are your thoughts about nature in the age of the metaverse?

CC: There is no replacement for the natural world, and we are destroying it faster than we can possibly scan it into a metaverse. The metaverse might become a place for humans to escape and live in imaginationland, but everything else is left to deal with the reality we have created on Earth.

There have been many discussions about how nature is a human construct, a way that we designate something as separate from us to be dominated. But we are nature too, not above or outside of it. We can put on our goggles and go into the cave and watch the wall, but we will still need to live in the natural world at the end of the day.

Also, personally, I would rather spend time in a quiet forest than in a virtual space with a bunch of people.

AM: What are your predictions for the future of art and technology?

CC: I hope we, as digital artists, remain a critical voice about where technology is going and how it is changing us. The funders of technological change right now are billionaires who prioritize making money over all else and have little regard for our collective future. We cannot allow them to define our narratives, and it is from the arts that better futures can emerge.

AM: Thank you!